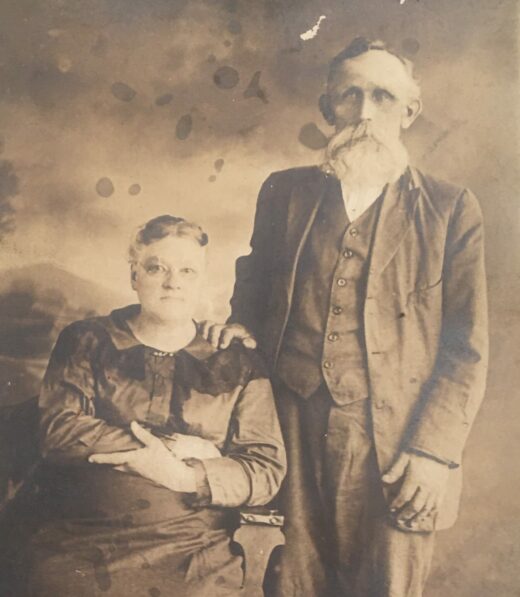

Quite often, I find myself thinking things like, “If not for this one thing having happened, I likely wouldn’t be where I am today.” I wonder, for instance, if my father hadn’t gotten into an accident that kept him from shipping off for Vietnam, how my life might have turned out differently. Or I start thinking about the fact that, if my great, great, great great, great grandfather hadn’t fought in the War of 1812, earning a land bounty that brought the family west to Illinois, where my grandfather would eventually meet my grandmother some 120 years later, I likely wouldn’t be here at all. And, today, as I sit here in front of the fireplace on a snowy day in Michigan, I find myself considering how the kindness of my great, great grandfather’s brother, John Calhoun Wise, and his wife, Sarah “Kate” Catherine Emerson Wise, may have saved another branch of my family from ruin more than 100 years ago… That’s John and Kate Wise in the above photo, and tonight I’m going to share some of their story, as told by their daughter, Mattie Belle Wise in the 1970s. [It kind of reminds me of something from Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House in the Big Woods.] But, first, here’s the context.

Remember how, earlier this year, I was telling you about my great great grandmother, Minnie Wise Florian, the fact that her mother passed away when she was just four years old, and the stories I’d heard of her father, Jefferson Davis Wise, having abandoned her around that same time, for reasons that have never been clear to me? Well, at the time of my last family history post, as you may recall, I’d found the 1900 census for Minorsville, Kentucky, which showed that my great grandmother, Minnie Wise, was, by the age of seven, living with the family her uncle, John Calhoun Wise. Well, I’ve been doing a little more digging since then, and I found that another member of the Wise family had the foresight some time ago to transcribe family stories that had been shared by my great grandmother’s cousin, a daughter of John Calhoun and Kate Wise by the name of Mattie Belle. She would have been less than a year older than my great grandmother, and, according to my aunt, who I just exchanged emails with, she and my great grandmother remained close for their entire lives… Before I get to that, though, here’s a photo of me with great grandmother, who we called Ma Florian. [As I’ve noted before, it was my Ma Florian, along with her husband, Curt Florian, who we called Pa, who essentially raised my father from the ages of 4 until he was about 12.]

OK, so here are a few excerpts from the Wise family history as related by Mattie Belle Wise. It not only does a pretty good job of describing farm life at the turn of the century in rural Kentucky, but also paints a fairly admirable portrait of her mother and father — the people who, it would seem, raised my great grandmother after her mother’s death. I should note that, in order to help with the readability, I’ve done just a bit of editing and shifting around of paragraphs. I don’t think, in so doing, that I’ve changed the meaning of anything, but I’d be happy to provide copies of the original transcriptions, should anyone have questions… With all of that said, here, in her own words, is the story of Mattie Belle Wise (1892-1992), with a few brief interruptions from me.

The only way we had to heat our house was by a fireplace, and that sure (took) some wood for the long winter. I used to help Edgar and Pa saw wood all winter. We just had a six months school. It began the first of July and was out by Christmas.

We never had a doctor… I remember the first doctor I ever saw. Mary Ann (got) real sick and Pa went for the doctor. He came on horseback. He had on a black suit, frock tail coat, (and) stove pipe hat. (He) had long whiskers, and nose glasses with a string fastened over his ears. In my mind I can see him now. I had never seen a man like that. I was my mother’s fifth child, and the first one that she ever had a doctor for. When the child was born, she had a midwife. Old grandma Traylor was a midwife, but by the time I was born, she was to old to practice.

The Edgar that she mentions here would have been her older brother, Edgar Emerson Wise, who was born in 1887, and died in 1982. [Edgar was married to a Bessie Roberts Wise, who I think I may have heard of as a child. At least I seem to recall hearing my Ma Florian talking about a Bessie.] And the Mary Anne referenced here would have been the sister of Mattie and Edgar, who lived from 1885 to 1960. [So I guess the doctor in the frock tail coat was worth the money.]

When my parents were married, Pa had a cousin, and he and his wife had separated. They had five boys. The oldest was only six. And my parents had taken him before they had any of their own. He lived at our house until he was seventeen. Then, on down through life, they took in everybody that did not have a home. Grand Hancock lived at our house fifteen years. He worked for Pa for $15.00 a month, but he never had any other home. And Jodie Breaden worked there seven years. He never had any other home. He never left until he married Perry’s sister Nelly Neal. She died in Shirley, Indiana, when her first baby was born.

(My parents) never turned an orphan away. After we were all married and gone, a boy they knew through the church told Mama that the woman that had him was going to take him back to the orphans’ home so she could get married again. My folks only had a horse and buggy, and they got a man with a car to take them to Louisville to the orphans’ home. And, when Mrs. Perkins brought him in, my parents signed up for him, and (took) him home with them. He lived with them for 9 years…

Maybe it was self-serving to some extent. Maybe they needed people to help on the farm. Still, though, my sense, given all of this, is that these were two very decent people, and it helps explain why, according to the records I’ve been able to find, my great grandmother came to be living with them after having lost her mother. [According to later census records, it looks as though she would eventually move in with her older brother, Grover Cleveland Wise, but my sense is that she grew up with John Calhoun and Kate, and likely even came to think of them as her parents. In fact, the caption of the photo at the top of the page here, written in my grandmother’s handwriting, identifies them as “Pa” and “Granny”, along with a note saying, “Mother (lived) a long time with (them while) growing up.”] Here’s more. [I found it really sweet that my grandmother, Gladys Florian Phillips, referred to them as Pa and Granny. Maybe I’m reading too much into it, but I find that telling.]

We had a long way to go to school (as children). We walked in the summertime, and, when winter (came), we drove a horse and “surry. We would pick up so many children along the way that they would be hanging onto the sides of the surry. We had an old maid teacher. Her name was Crocket Henry, and if there was even one child in school that liked her, I never knew it. She live in Versailles, and drove a horse and buggy to school. She brought hay and corn to feed her horse. The boys would unharness him, and put a hitch rope around his neck and tie him to a tree (for her). One day, (that horse) went around and around that tree until he fell, choking to death. Two of the boys ran out, and one pulled the rope away from his neck while the other one cut it two with his knife. It was in such a close place to cut, he cut the finger of the boy who was holding the rope. It was several minutes before the horse could get up. Then Miss Henry called the boy in who had used the knife, and gave him a hard whipping for cutting the other boy. But that cut had not amounted to anything.

The school house was a one room house built in Mr. Broadhead’s pasture. The Broadheads were rich people. We had to carry the drinking water from the Broadheads’ kitchen at least a half mile. Two children always had to go to carry that big bucket back. Every child was always anxious to go. The negro cook always gave us cookies or beat biscuits. They were the only ones I ever saw, but they were delicious. They were a little larger than a silver dollar, and three-fourths of an inch thick. They tasted something like a cracker, only a lot better…

One more thing I want to tell about was us living at the old Ford place, where we got our water from a spring house. I suppose it has a 20-foot square rock house underground. You had to go down 21 steps hued out of the stone from the ground to the basement. You could dip your bucket in the water. It ran over a flat rock 12-feet square before it ran into the basin. We always had plenty of cold water, and we kept our milk in gallon crocks sitting on that rock. The outlet for the water was a cave about 3-feet high. You could not see where it went, as it was dark. One morning, before daylight, we were up, getting breakfast, and (we had to have) some water. I (took) my bucket and started for the spring. You had to go through the yard and part of the barn lot. I had (gone) down about 10 of the 21 steps when I stepped into the water. I backed out and went to the ground spring in the barn lot and got the water. We had had several days of rain and the water had backed up in the cave and filled our spring house. It was several days before the water subsided. Then we had a messy spring house to clean up. But, when we scrubbed it all out, the water from the spring was as clear and cold as ever.

We moved back to Scott County, Kentucky in 1908 with three less in our family… to our farm. The house was a mile off the road, over in a hollow. There were hills all around. I was 16 years old this time, but we went home with no debt over our heads. My father’s father died in 1890, and my dad had bought out all the other heirs. But he’d never taken possession of the farm as long as his mother wanted to live there. Uncle Roe and his family lived there for years, then uncle Jeff and the two of his children had moved in with her. Then, in 1909, she had a stroke, and could not take care of herself. My dad and myself put a feather bed on a sled and moved her to our home. Then he (took) possession of the farm. Grandmother’s house had always been a two-room log cabin with a shed built for a kitchen, and a log smokehouse. My folks wanted to move out on the road (though). We cut trees out of our woods, and I helped my Dad saw every log into board lengths. Edgar and Cleve hauled them to Elmsville to a saw mill, and had them sawed into boards. They would take a load of logs to the mill and bring back a load of lumber. John Baker and Wister Curtis tore down the old log house, and built a new one with three rooms, and two porches, and two rooms upstairs, with a smokehouse, and an outside toilet. And, in a steep bank, they dug a milk house with a cement floor, and walled it up with rock, and covered it over with dirt and then sodded it. We kept our potatoes, turnips and apples in there all winter, and kept our milk and butter in there in the summertime. We never heard of a refrigerator at that time.

The “uncle Jeff” mentioned above would have been my great, great grandfather, Jefferson Davis Wise. And the “Cleve” mentioned would have been his son, my great grandmother’s brother, Grover Cleveland Wise. According to that same 1900 census I referenced earlier, while Minnie was living with her aunt and uncle and their family in Minorsville, her father, Jefferson Davis Wise, was living nearby with his mother, Matilda Gill Wise, and his son, Wythe Thomas Wise. So, when Mattie talks above about the two-room log cabin that her grandmother lived in with “uncle Jeff” and two of his children, that’s who she’s talking about. [I’m not sure which other child was living with them. According to the 1900 census, it was just Matilda, Jefferson and Wythe living in the old family home. I’m guessing it must have been Cleve, as he was the Jefferson’s only other child at the time. There would eventually be a half-brother, named Seth, whose mother was a later wife of Jefferson’s, but he wouldn’t be born until 1902.]

I should add here that I’m still not sure about the relationship between my great, great grandfather and Minnie Wise, or why she came to be living with Jefferson and his family. It could have been because Jefferson and Kate had daughters of roughly the same age, or it could have been that he wanted her to have opportunities that he couldn’t give her, and felt as though his older brother could. Or, of course, he could have just been a terrible father, which is more in-line with what I’ve heard through the family, which is that he “abandoned” my great grandmother. Still, though, given that he remained living close-by, in Minorsville, I’m inclined to think that he may not have been too terrible. I suppose there’s no use in wondering about it, but I am curious as to why my great grandmother either left, or was forced to leave, when her brothers continued to live with their father. And I’d be curious to know why Jefferson moved into my great, great, great grandmother’s two-room log cabin. Was he forced to live with her, as he had no where else to go, or was he there because she needed him? Again, I’m sure I’ll never know, but it’s something that I keep coming back to as I spend time going through these documents. My guess, and I could be wrong, is that, when he wife died, it was decided that he and the boys would move into the two room log cabin with his mother, and that my great-grandmother would join the family of his brother, who had more space, and several daughters of his own. Of course, Jefferson may also have been a terrible man who my great grandmother wanted to get away from… Here, I’m told by someone else doing ancestry work online, is the home of John and Kate Wise in approximately 1913. [My great grandmother would have no longer been living with them by this point. As you may recall from past posts, she was living with her brother Cleve in Switzer, Kentucky by the time of the 1910 census, and she was married to my great grandfather by 1912.]

OK, here’s more from Mattie Wise, talking about the new house the family moved into in 1912, which I suspect is the house we see above.

We moved out on the road on January 20, 1912. My mother said that they had moved into three new houses in their married life, and moved into each of them on the 20th of January.

My grandmother died in September 1913. (Around) the time we moved, and that she died, two preachers from Gas City, Indiana (came) there preaching that the Church of Christ was the right and only church. My mother and father, and all their children, and grandmother, all came into the church, and at least half of the Minorsville church came in (with them). We did not have a house to worship in, though. We built a bush arbor, and used that until the weather got too cold to meet. By that time, Mr. Jim Moody, (the father-in-law of one of the Settles’ boys, gave us an acre of ground on top of a hill. And, by winter, we had moved into a new church which we called Ceserea. Thank God, in 1979, it’s still a strong church. Every time we go back to Kentucky, I just love to attend church there. George and Jennie Wise live in Georgetown, and they always come and take me to church.

OK, and here’s the part about the flu of 1918, and the damage it did in Franklin County, Kentucky. This is the first story shared by Mattie where my great grandmother, Minnie, is mentioned by name.

Things went along pretty well until 1918 and the flu broke out in Franklin County. It was a really bad one. Sunday morning, there at Woodlake, there were seven houses with corpses laying in them. Cleve Wise died one Sunday morning, and their three year old boy died the next Sunday. Cleve went over to his sister’s, Minnie Florian, as they had all had the flu and lived through it. He thought, if he went over there, his family would not (get) it. Carrie was down at mother’s when Cleve was taken sick. She had taken the two babies and went home. In a few days, I went up to stay with her babies so she could go and stay with Cleve. It wasn’t but a few days until Pa brought her home with a temperature of 104. Then, the following Sunday, Cleve died with pneumonia. I went to Carrie’s in November and stayed until March. Then they moved back to Minor Branch. Carrie had a hard time keeping a home and raising seven children. Cleve had his life insured for $1,000, which helped her out a lot.

I rode a horse back and forth to school a lot of the time, and I had to go through Carrie’s farm one morning.I stoped by Carrie’s house. She had such a sick headache that she could not (sit) up. All the children had gone to school (except for) Edna (who) was just six months old. I just fixed her two or three bottles, wrapped her up in a baby quilt, and (took) her to school with me. In going, I had to lay down a rail fence for the horse to get over. I could not get off the horse with her, so I just told my horse he was going to have to jump the fence. I pulled up on my bridal and gave him a little kick, and he jumped the fence like he had too. When I got to school, I put her quilt under my desk and gave her her bottle. Never had one bit of trouble with her all day, and, going home in the afternoon, I made the horse jump the fence again. Then, that winter, the flu broke out down where we lived. No one died, but sometime the whole family would all be down at the same time. One family that lived on the hill above us had all five children and the mother and father all down with it. My mother killed a lot of hens that winter. I would take a bucket of soup and go feed a family, comb the women’s hair, fix up their beds, carry in enough wood to do them until I could get back the next day, then I would go back home, get another bucket of soup, and visit another family. Sometimes I would not get home until 2:00 in the morning. My mother said my dad never went to bed until he could hear the horse’s feet on the pike coming home. I kept that up all winter, and never as much as had a cold. That was the winter of 1918. When I stayed with Carrie, I wore a mask over my mouth and nose at all times. The Red Cross furnished the mask and the doctor brought them out to me. The flu was much worse in the winter of 1918. No undertaker would go in the house. When Estel died, Mattie Lee Wise was with me that night. The undertaker brought the casket and set it on the porch. We washed and dressed Estel, (took) him out, put him in the casket, and the undertaker came got him for burial. He died in the same room with his mother. When she came to enough to tell that his bed was made, she just said, “the little fellow is gone,” and then she lapsed into unconsciousness again. It was several days before she really realized he was gone.

According to my great grandfather, Curt Florian, he survived the flu of 1918 by staying drunk for the duration of it, and doing the work of every other farmer in the area who had fallen ill… Here’s more from Mattie Belle Wise.

Carrie moved back to Minor Branch. She had a two room log home with a shed room built on for a kitchen. It had one large room upstairs. The first Christmas they were there, we planned a big Christmas. We cut a big cedar tree, and drug it upstairs and decorated it with pop-corn, cranberries and colored paper. And, oh yes, we had real candles on it. My mother and father were coming for the celebration, and, just before they got there, we (lit) all the candles. And, when my dad came in, he could not believe his eyes… in an upstairs room of a 500 year old house with a cedar tree and lighted candles. He was as particular to put out each candles without letting them touch the tree. Then he sat us all down and gave us a lecture that we never forgot. They raised eight children of their own, and, in the meantime, gave homes to three orphan children.

And here’s more about my great grandmother, Minnie Wise… who, I guess, may have been a bad influence on her cousins.

Minnie Wise lived with us for a while. I was just seven months older than she was, and Hat (Hattie) was three years older than myself. And, naturally, we three were venturesome. I remember one time… We had a big barn. In the winter, it housed all over stock; the horses, cows, hogs and sheep, and we always filled the lofts with hay. We three girls had taken matches and paper up in the loft and rolled cigarettes out of clover bloom, which we smoked. My brother caught us, and told us the danger of smoking up there. He said, if we would promise never to do it again, he would not tell Pa. We promised, but, in a few weeks, we did the same thing again. He caught us again, but he did not let us know it. He went to the house and sent Pa to the barn. Well, we really got a good dose of apple tree tea. And, from that day to this, I have never smoked.

One time I remember smoking my grandmother’s pipe, though. My grandmother had a sister that lived close to us, our aunt, Liss Redding. She never had any children, and we children just loved to go spend the night with her. One night I went to spend the night, and my grandmother was there, and I wanted to smoke her pipe. She told me it would make me sick, but I insisted on smoking it anyway. I sure paid for it. I layed on a pallet on the floor and vomited all night. Needless to say I learned another lesson. It was a stone pipe with long green tobacco. that was tobacco we had raised, which had just been hung in the barn to cure.

We moved out on the road on January 20, 1912. This new house we had built had a front porch with a flat tin roof. You could step out the upstairs window onto the porch’s roof. And it gave us an ideal place for drying apples and green beans. We would spread down tobacco canvas, which was a covering we had to cover the tobacco plants with, on the roof, and then put our apples on that, and then cover the apples with more canvas to keep the flies and bugs away. And they would almost dry in a day. I remember several nights when the weather was hot, Katye and myself would put a feather bed out on top of the porch and sleep out there.

When we moved out on the pike, all the children were married (except for) Lida, Katye, and myself. Then Lida married. We bought 60 geese from one of our neighbors, and Katye and myself sure had a job (over) six weeks in the spring and summer. You have to pick geese. We made a lot of new pillows, and some new feather beds. My mother would sew up a sheet and leave a small opening for us to put the feathers in. And we’d put that sheet in a barrel. We would drive all the geese into the barn, and, when we picked one, we would put it outside. It was an all-day job, picking these 60 geese. You hold their feet in your hand behind their back, and put their head under your arm, and pull the feathers from their breast. You never picked their back, and you had to leave what was called the “bolster feathers” for the geese to rest their wings on. So you had to know what you were doing, or you would have a lot of (drooping) wings. But we enjoyed life.

We always made a big ta-do about my parents’ birthdays. My dad’s was July 1, and my mother’s was November 4. We always fixed a big dinner and invited all the kinfolks and neighbors in. We would take a barn door off the tobacco barn, and make a table out of it. Sometimes, when the married children came home, so many would stay all night that we would take two feather beds and put them on that table, and let the children sleep outside. A grown person would sleep on the end of the table to keep the children from falling off. But those days and times are gone. When I was a very young girl, I learned to knit piece quilts, tat, weave and crochet. I was the only one of 7 girls that learned to make tatting. Now I am 87, and spend what could be many a lonesome hour tatting. I don’t know what I will do with all of it, but maybe some of the younger ones would want some pillow cases with tatting on it.

My father’s mother had a large family. She raised 10 children. One died when a baby. My grandmother had 7 grandchildren. And, on my mother’s side, my grandmother had 11 grandchildren. My mother’s parents died when my mother was very young. My mother was three when her mother died. She left three girls and one boy, and one half-brother. There were eight of us children, but we only had three cousins on my mother’s side. One of her sisters died in childbirth, and her other sister never had children. Her brother, Jim Emerson, had three children.

Well, I’ll start another chapter in my life. Katye married Otis Kidwell, and that left only me at home. Lida and Bute both married at 15 years old, and I did not care if I ever married. Our dad was always strict on us girls. Katye and myself were both teaching school, and Pa would not let two boys come there in the same car and take us to church. We had to drive our own horse and buggy. The boy I went with had a younger brother, and the boys would bring him along. And, as soon as we got out of sight of the house, the little boy would drive our horse, and we would go in the car. He never let us go to a dance. Whenever we got to go, it was always just a party. I went with one boy nine years and never did get to go any place with him. His sister was my best friend, and they would let me go any place with her as long as we drove our horse and buggy. His name was Steward Hearty. By this time I was “an old maid” school teacher. I was teaching at the Sash School, and had a pie supper one night. We had pie suppers. All the young girls baked pies and brought them, and the boys bought them. We used the money to build up our library in the school, as we had no other funds. So, that night, Perry Neal came to my pie supper and the boys made him pay $4.00 for my pie. Such a thing had never been heard of. Well, that was the first time I ever saw Perry Neal. Then, a few weeks later, Hettie Lou Roberts was teaching school at Minorsville, and she had a pie supper, and I went and taken a pie. And, that night, they ran my pie up to $7.00 on Perry. And he asked me to let him take me home, and I excepted, as there were five of us in one buggy. That was July of 1922. He took me to church, and everywhere I had to go. And, one Saturday morning, I had to go to Georgetown to a teachers’ meeting, and we stopped in Stamping Ground at a preacher’s house and got married. He had to call the cook in from the kitchen to be a witness. Oh, yes, we had it all planned. I was 29, and Perry was 35, and I made him ask my parents’ consent for us to marry. I was the last. I got Carrie to teach for me, and I (took) off a week. We went to Katy’s Saturday night for supper, and I never sat down to such a supper. She had two negro women in for two days preparing everything. I think there were twenty at the table, and a party afterwards, and it began to sleet, and some could not get their cars started. The party broke up at 2:00. Then we went to Tom and Lida’s, to Hat and Nat’s, to Edgar’s, and to John and Mary Ann’s, and back home by the (end) of the week. That night at Lida’s, there were a bunch of boys stripping tobacco. They all knew Perry, so they tied a cowbell to the springs of our bed, but I went to bed first and found it. I very gently untied it, and set it aside, as I ruined their fun there, but they did ride Perry on a rail that night.

Looking back over my childhood days, there were happy days. We never had much money, but a little went a long way in those days. We raised wheat for our flour, and corn for our meal, and cane for our sorgum, and killed hogs for our meat and lard, and had plenty of milk and butter. Our father was a good worker as well as a good manager on the farm. My mother was a wonderful woman. She dried apples and beans in the summertime, and canned blackberries and all kinds of fruit for winter use. Berries grew wild, and we children would all take our buckets early in the morning, and go to the woods and fields, and would come in at noon with a load of berries. Then mother would can them. She made sauerkraut out of cabbage, and our garden looked like an Indian campground. There were so many teepees. We would bury potatoes, cabbage, turnips, parnsnips and apples, enough to (last) us all winter. You would clear off a spot of ground, cover it with straw, about a foot think – and we always had plenty of straw, as we thrashed our own wheat – then we would cover the vegetables about a foot deep, then set boards up around them all coming to a point in the center, and then cover the whole mound with dirt a foot thick to keep from freezing. And anytime in the winter, when the snow covered the earth, we had plenty of fresh vegetables.

Our parents always sent us to school. My mother never got to go to school, and she was determined her children would all go. Her parents died when she was very young, and she was shifted from one home to another, until she was eleven years old and her sister Mary was thirteen, and my father’s uncle, Sam Wise, and his wife, Amanda, (took) the girls and gave them a home until there were both married.

My parents had seven girls and one boy. My mother (did) all the sewing and cooking. We girls learned to sew and knit. We had sheep, and we would sheer them, and take the wool to market and have it corded – that was to make it into rolls, three feet long and one half inch in diameter – and my mother would spin it into yarn, and we would all knit our own stockings. Some of it she made into finer yarn by pulling the roll tighter as she spun it on our loom. We wove linen and made all our own petticoats, and blankets, and carpets. Only two of us girls ever wove on the loom, Mary Ann and myself. I have woven hundreds of yards of carpet for other people. They would pay me 10-cents a yard for weaving.

In growing up, we children used to love to play in the woods. My mother would fix us a gallon and half bucket of food – sausage and biscuits, biscuits with butter and blackberry jam – and we would go to the woods early in the morning, and take all the smaller children. We would even take the baby, and take a quilt for her to take her nap on. We would hardly ever go home until sundown. There was a spring of good cold water in the woods. Since I became a mother, I often think what a blessing that it was to our mother to have all those children out from under foot all day. We raised horses, and could hardly wait for the young colts to get old enough for us to ride. We children could ride them long before they were strong enough for a grown man to ride. Our dad was very careful. He was always there when we wanted to ride.

We lived a mile off of the road, and always had to walk out to the road to go anywhere, or to go to school. We had to cross Minor Branch in going to school. And, if the creek was up, our dad would take a horse and set us all across the creek. Then we would walk on to school. Sister Hattie and myself were always tomboys. There were so many girls, and just one boy, so we always worked out on the farm. We had some pretty steep hills. My dad mowed them in the summertime for hay for the stock, and, in the wintertime, they made nice smooth slopes to sleigh ride on. I remember one time, there had been a big snow, and it had began to melt, and the branch at the foot of the hill was running full of ice and snow. Hat and myself taken the sled, and went up on the top of the hill for a ride. Hat said she could stop the sled before we got to the bottom of the hill, but we gained such speed going down the hill she could not stop. Well, we went in that creek (up to our) head and ears. But she never turned loose of the rope on the sled. And, when she came out of the other side, she brought the sled with her, and we ran to the house. Our mother stripped us off (in front of) the fireplace, and gave us a rub down with a coarse towel, and put us in the dry clothes. Neither of us even (got a) cold.